What business owners should watch for when engaging a business broker

Selling a small business is usually a once-in-a-lifetime transaction. For many owners, it represents years—or decades—of work and often their largest financial asset.

Yet, most owners sign a brokerage contract before they fully understand how broker incentives work, what is standard in the market, and where contracts can quietly shift risk from the broker onto the seller.

This article outlines common brokerage contract clauses, their legitimate purposes, and when they cross the line into predatory territory.

1. Minimum Fees & Termination Penalties

Many brokers include a minimum fee as part of their engagement. This is not inherently problematic, but the appropriateness of a fixed fee depends heavily on the size and complexity of the business being sold.

A minimum fee (often called a retainer or upfront work fee) should exist to:

- Demonstrate the seller's commitment to the process; and

- Cover the broker's reasonable, out-of-pocket costs (valuation work, marketing materials, CIM preparation, data room setup) relative to the scale of the business.

What is reasonable for a $5 million business with multiple locations, employees, and financial complexity is not reasonable for a $500,000 owner-operated business.

A minimum fee should not exist to guarantee the broker a profit if no transaction closes.

What's market: A modest upfront retainer—scaled to the size and complexity of the business—that is often credited against the final success fee, and/or a minimum commission "floor" (e.g., "10% of the sale price or $30,000, whichever is greater") payable only upon a successful closing.

Red flags: Clauses that require the seller to pay a large lump sum simply for cancelling the engagement or taking the business off the market, regardless of whether a buyer was sourced or a transaction completed. These provisions sever the link between compensation and performance, weaken the broker's incentive to execute effectively, and shift execution risk almost entirely onto the seller. A broker who is paid for non-completion is no longer economically aligned with the outcome the seller actually cares about: a successful closing.

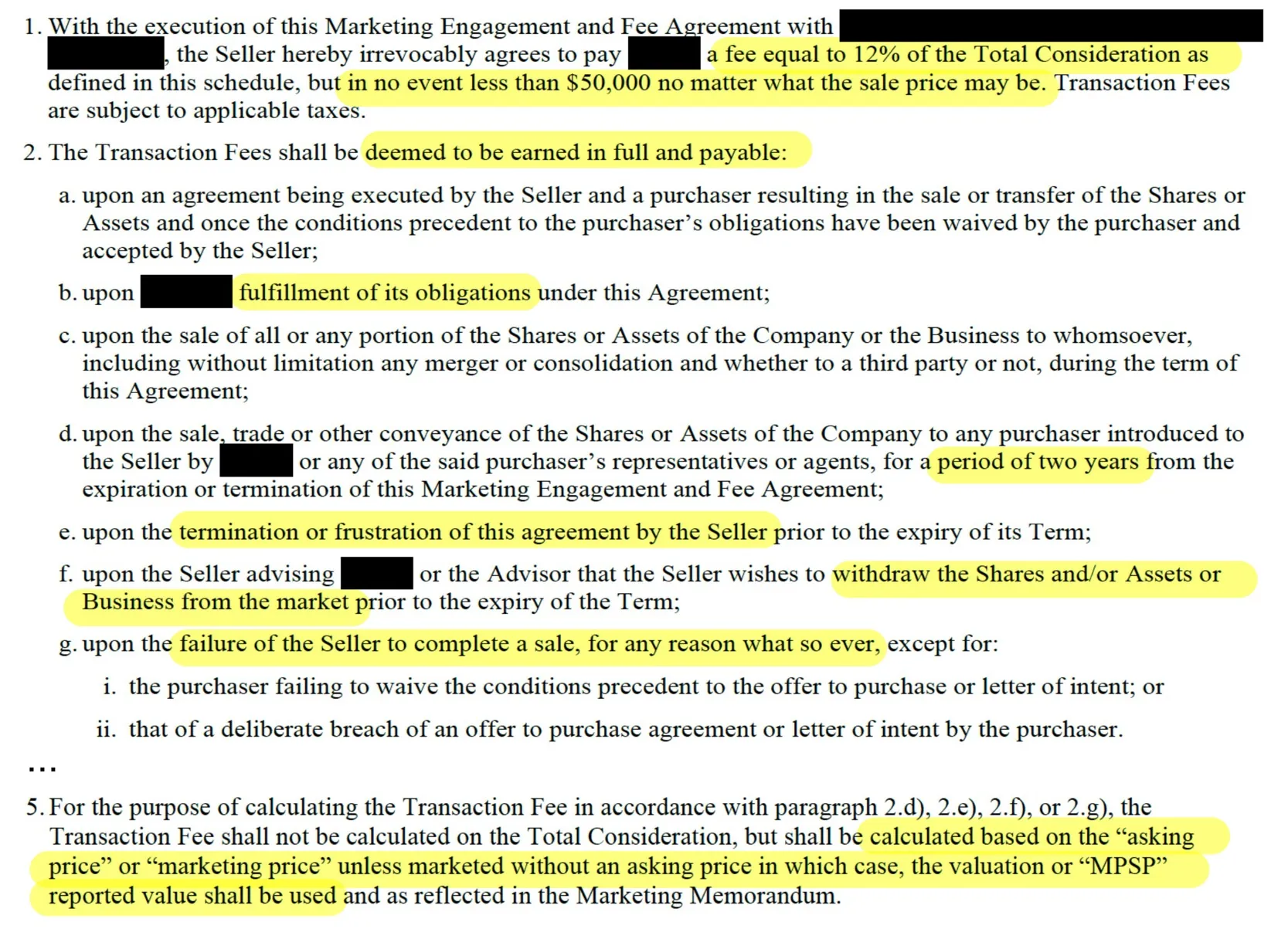

Example: If a broker values a small, owner-operated business at $600,000 and requires a $50,000 "minimum fee" that becomes payable if the seller terminates the engagement or the business fails to sell, that is not a cost-recovery mechanism. It is effectively a guaranteed ~8% commission, regardless of outcome.

By contrast, a modest fixed fee that reflects the actual work required—rather than a percentage of enterprise value—is far more consistent with market practice.

2. Success Fee Triggers

A success fee should incentivize and reward the broker for exactly that—success. A broker should earn a commission only when they successfully sell the business.

That's it.

What's Market: For Main Street businesses, an 8–15% success fee earned only if a transaction closes, with the fee payable at closing from the proceeds of the sale.

Red Flags: Success fees triggered without a closing. A success fee should be earned for one thing only: successfully closing a transaction. Any clause that allows a broker to earn a commission when no sale occurs breaks this core incentive structure.

Several contract provisions attempt to do this in different ways:

- "Ready, Willing, and Able" clauses

More common in real estate, these provisions state that the broker earns a fee if they introduce a buyer who claims to be "ready, willing, and able" to purchase at the asking price—even if the seller ultimately decides not to proceed or no transaction closes. - Withdrawal-based triggers

Clauses that require the seller to pay the success fee if they withdraw the business from the market due to illness, personal circumstances, or changing market conditions. - Financing failure triggers

Provisions that make the seller responsible for the broker's fee even when a deal collapses because the buyer fails to secure financing or satisfy other conditions. - "Fulfilled obligations" language

Vague clauses stating that the broker earns the success fee once they have "performed their obligations" (such as marketing the business), regardless of whether a buyer closes.

While these provisions differ in form, they share the same effect: the broker gets paid without delivering the outcome the seller cares about. When compensation is no longer tied to a completed sale, the broker's incentives are no longer aligned with the seller's objectives.

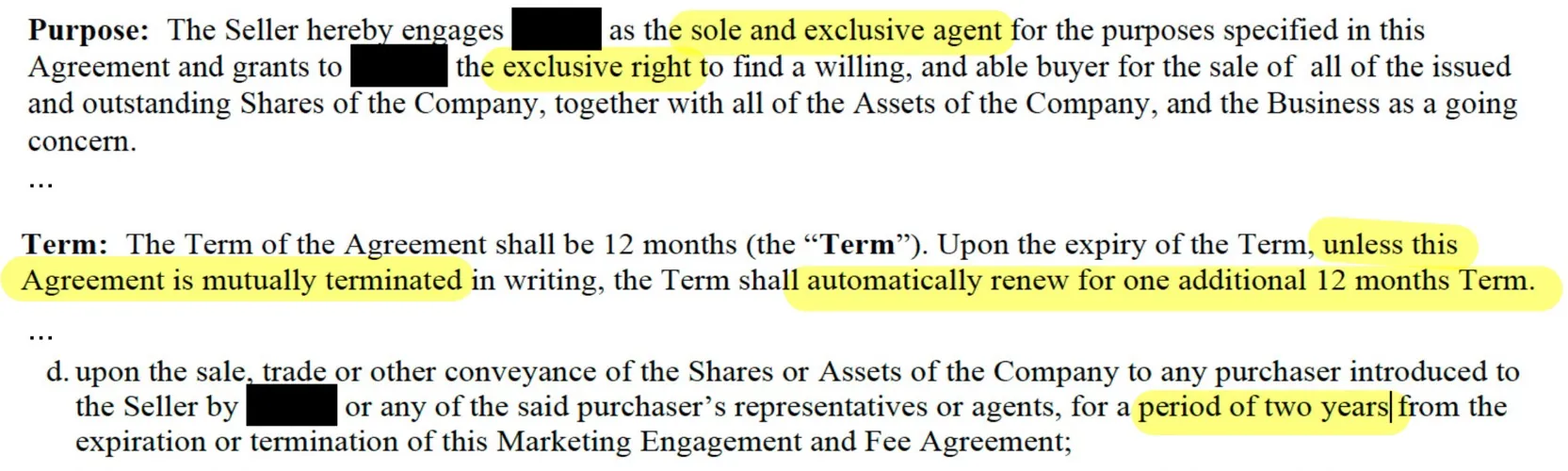

3. Tail Periods

A "tail period" is a window of time after the brokerage contract expires during which the broker is still owed a commission if the business sells.

Its legitimate purpose is to stop sellers from circumventing the broker—i.e., meeting a buyer introduced by the broker, waiting for the contract to expire, and then closing the deal privately to avoid paying the commission.

What's Market: A 12-month period that applies only to buyers the broker can document they introduced, sent a CIM to, or actively negotiated with. The broker should provide a specific list of these names within 10 days of contract termination.

Red Flags:

- Tails longer than 12 months.

- Universal Tails: Clauses that apply to any buyer who purchases the business after the contract ends, even if the broker never met them.

- Broad Definitions: Defining "introduced" to include anyone "associated with" a prospective buyer.

Real example of red flag language:

4. Exclusivity & Automatic Renewal

Broker exclusivity is standard. Brokers invest significant time and money upfront (marketing, valuation, vetting buyers) with no guarantee of pay. Without exclusivity, a seller could let three brokers do the work and only pay the one who crosses the finish line first, which disincentivizes quality representation.

However, while exclusivity is fair, indefinite exclusivity is not.

What's Market: An exclusive period of 6 to 12 months. When that period ends, the contract should expire or require a mutual written agreement to renew.

Red Flags: Evergreen Clauses (Automatic Renewal): Clauses stating the contract automatically renews for another 6–12 months unless the broker and seller mutually agree to terminate, or the seller cancels within a strict, small window (e.g., "between 30 and 45 days prior to expiration").

These clauses unnecessarily remove the seller's ability to reassess performance at the end of the exclusivity period and to decide—based on results—whether continuing the relationship makes sense.

Real example of red flag language:

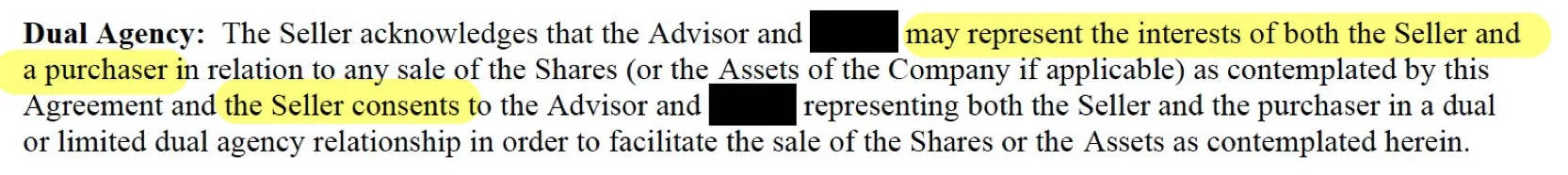

5. Dual Agency

Dual agency means the broker represents both the buyer and the seller in the same transaction.

In residential real estate, dual agency is relatively common because the broker's role is largely transactional and standardized. In business sales, however, brokers are deeply involved in advising on valuation, deal structure, timing, and risk allocation. These elements directly affect price and outcomes for both sides.

A broker cannot simultaneously advise a seller on maximizing value and negotiating leverage while also advising a buyer on minimizing risk and purchase price. The conflict is structural, not theoretical.

In our opinion, reputable business brokers should not undertake dual agency mandates.

What's Market: The broker represents the Seller. The Buyer signs a disclosure acknowledging the broker represents the Seller's interests, and the Buyer is encouraged to get their own representation.

Red Flags:

- Pre-authorization: Clauses that pre-authorize dual agency and waive conflicts of interest before a buyer is even identified.

- Vague Duty of Care: Contracts that do not specify how the broker handles confidential pricing strategy if they end up representing the other side.

Real example of red flag language:

Final Takeaway for Business Owners

Before signing a brokerage agreement, ask one simple question for every clause:

Does this clause exist to protect legitimate work—or to protect the broker from accountability?

A Market-Standard Contract Checklist:

1. Minimum fees are reasonable and proportionate

- ☐ Any upfront or fixed fees are modest and designed only to cover reasonable costs—not to guarantee the broker a profit if no sale closes.

- ☐ Cancelling the engagement or withdrawing the business does not trigger a large lump-sum payment or disguised commission.

2. Success fees are earned only upon a closing

- ☐ The broker earns a success fee only if a transaction actually closes and proceeds are received.

- ☐ There are no "ready, willing, and able," withdrawal-based, financing-failure, or "fulfilled obligations" clauses that trigger payment without a completed sale.

3. Tail periods are narrow, documented, and time-limited

- ☐ Any tail period is limited (typically no more than 12 months).

- ☐ Post-termination fees apply only to specific buyers the broker can document they introduced or actively engaged.

- ☐ The broker provides a clear, written list of tail buyers upon termination.

4. Exclusivity preserves seller optionality

- ☐ The exclusivity period is finite (typically 6–12 months).

- ☐ The agreement expires at the end of the term unless both parties affirmatively agree to renew.

- ☐ There is no automatic or "evergreen" renewal that limits the seller's ability to reassess performance.

5. Representation is clear and conflicts are not pre-waived

- ☐ The broker represents the seller only.

- ☐ There is no pre-authorization of dual agency or blanket waiver of conflicts before a buyer is identified.

- ☐ The contract clearly addresses how confidential information and negotiation strategy are handled.

If you're unsure whether a clause is market or not, get a second opinion before signing. Once signed, your leverage disappears.